Operads: first contact

An operad is a monoid for the substitution product discussed in lecture 3. As such, “the theory of operads” is the study of the category $\mathbf{Opd}={\bf Mon}({\bf Spc},\circ)$; but things are never as simple as they seem…

Some more intuition on the substitution product

The operation of substitution can be given a combinatorial meaning as follows: an $(F \circ G)$-structure on a finite set $U$ is defined by a triplet $(\pi, x, \vec\gamma)$ where:

- $\pi$ is a partition of the set $U$, which is divided into a collection of disjoint non-empty blocks $(U_1,\dots, U_n)$.

- $x\in F[n]$ is an $F$-structure on $U$; This structure is placed on the set $[n]\cong {U_1,\dots, U_n}$ of blocks that constitute the partition $\pi$.

- A collection of $G$-structures $\gamma_1,\dots,\gamma_n$ where $\gamma_i \in G[U_i]$ for all $1\le i\le n$.

The set of all $(F \circ G)$-structures on $U$ is formally expressed as the disjoint sum over the set of all possible partitions $\pi$ of $U$ of the product of the $F$-structures on the partition and the $G$-structures on each block:

Fundamental Combinatorial Examples

Several essential combinatorial species are defined or characterized through this substitution operation:

Example (The Species of Endofunctions). Every endofunction on a set $U$ is uniquely represented as a permutation of disjoint rooted trees. This is expressed by the combinatorial identity $End \cong S \circ \mathfrak a$, where $S$ is the species of permutations and $\mathfrak a$ is the species of rooted trees.

Example (The Species of Permutations). A permutation is defined as an assembly of disjoint oriented cycles. This follows the identity ${\cal S} \cong E \circ {\cal C}$, where $E$ is the species of sets and $\cal C$ is the species of cyclic permutations.

Example (The Species of set Partitions and Ballots). A partition of a set is defined as a set of non-empty disjoint sets. This corresponds to the identity $Par \cong E\circ E_+$, where $E$ is the species of sets and $E_+$ is the species of non-empty sets.

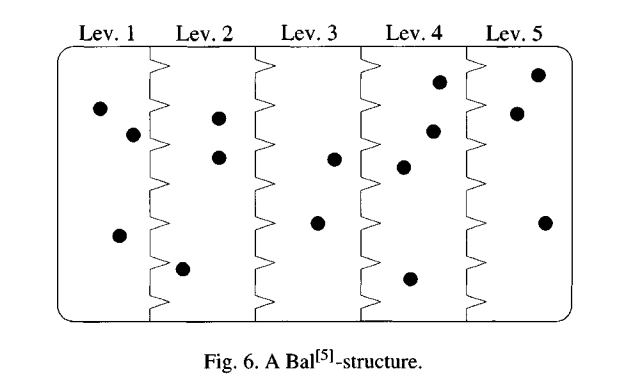

A ballot, or ordered partition, is defined as a linear ordering of non-empty sets. This satisfies the equation $Bal \cong L \circ E_+$, where $L$ is the species of linear orders.

Now, with the definition in hand, and algebraist’s goggles on, let’s flesh out what the definition prescribes. An operad consists of a functor $T : {\bf B} \to \bf Set$, equipped with

-

multiplication, a natural transformation of type $\mu : T \circ T\Rightarrow T$, subject to the associativity axiom (the two compositions are mediated by the associator):

-

unit, a natural transformation of type $\eta : J \Rightarrow T$ which satisfies the left and right unit axioms (mediated by the unitors):

It is worth noting explicitly the shape of $\mu,\eta$; those who already know it will recognize the form of an operad as defined in, say, algebraic topology textbooks.

- $\eta$, as a natural transformation of type $y1 \Rightarrow T$, corresponds by Yoneda to an element $u\in T1$.

- $\mu$ is a natural transformation in the set

where the last equality is Yoneda, and thus $\mu$ has components

Remark. Naturality for $\eta$ is straightforward; note that naturality for $\mu$ amounts to the commutativity of the diagram

given permutations $\alpha, \beta_1,\dots, \beta_m$, where $\bar\beta=\beta_1 \mathbin{ш} \beta_2 \mathbin{ш} \dots \mathbin{ш} \beta_m$ is the shuffle (шафл) of the permutations $\beta_1,\dots, \beta_m$.

Associativity of $\mu$ is better appreciated through a picture: given an $n$-ary term $f\in Tn$, terms $g_1\in Tp_1,\dots,g_n\in Tp_n$, and moreover terms $h_{1,1},\dots, h_{1,q_{p_1}},\dots, h_{n,1},\dots, h_{n,p_n}$, the two graftings depicted below are equal.

The associativity axiom, in diagrammatic form, assumes the following perverse shape: to be completely clear, denote $\mu^m_{k_1,\dots,k_m}$ the multiplication $Tm \times Tn_1 \times\dots\times Tn_k$, and suppose given suitable integers $h_{11},\dots,h_{1,n_1},\dots h_{m1},\dots, h_{m,n_m}$. Then the square

has to commute. Left and right unit are expressed, instead, by the commutativity of the two triangles

Proposition. Every operad $T : {\bf B} \to {\bf Set}$ defines a monad $\flat T : {\bf Set} \to {\bf Set}$ as follows:

- the underlying endofunctor $\flat T$ is

evidently, $\flat T$ is the analytic functor associated to $T$, so the construction of this proposition can be summarized as: the analytic functor associated to an operad (qua species) is a monad, and thus an analytic monad.

-

the unit (component) $\eta : X \to (\flat T)X$ is defined through the unit of $T$,

-

the multiplication (component) $\mu : (\flat T)((\flat T)X) \to (\flat T)X$ is defined from the composition

where the last arrow is obtained, in turn, composing

Examples of operads

As is obvious, on the same set there can be non-isomorphic monoid structures; similarly, even if usually there is just one important implicitly understood operad structure on a species, there can be many. One example is the species of linear orders $L$: it is the associative operad ${\tt As}$ operad with respect to a natural composition operation, but it is also an operad ${\tt Zinb}$, the Zinbiel operad, with respect to a different structure.

Example. The species of singletons defines an operad since its associated analytic functor is the identity (which is a monad, of course!).

Example. The species of elements $J : {\bf B} \to {\bf Set}$ consisting of the inclusion defines an operad and a cooperad (i.e. a $\circ$-comonoid in $\bf Spc$); I am recording the proof since it is an interesting piece of work I couldn’t find in any reference so far. A formal reason why $J$ must be a cooperad is that the associated analytic functor $\text{Lan}_J J$ must be a comonad: the density comonad of $J$. In fact, establishing an explicit form for $\text{Lan}_J J$ will unravel both structures, so we embark in a

Remark. An explicit description for $\text{Lan}_J J$. It is well known that in order to compute $\text{Lan}_J J(X)$ for a set $X$, one has to compute the colimit of $J\circ \pi$ in the diagram

where the left square is a comma object; furthermore, the colimit of the composite functor $J\circ\pi$ is isomorphic to the set of connected components of its category of elements $\nabla(J\circ\pi)$, thus we are left to compute the latter object.

An object of $\nabla(J\circ\pi)$ now is a triple $(n,\varphi : n \to X,i\in n)$ (for all practical purposes, this is a pointed $n$-tuple of elements of $X$: thus, $0=\varnothing$ is not an element of $\nabla(J\circ\pi)$), and an arrow $(n,\varphi,i) \to (m,\psi,j)$ is a bijection $\sigma : n \to n$, such that $\sigma i=j$ and $\varphi = \psi\circ\sigma$. All in all, then, two objects of $\nabla(J\circ\pi)$ lie in the same connected component if and only if they define the same nonempty, unordered, pointed list, and $(\text{Lan}_J J)X$ seems to be isomorphic to the Cartesian product $X\times \mathbb N_+[X]$ where $\mathbb N_+[X]$ is the free commutative semigroup on $X$ (its elements are nonempty unordered lists). We know from formal reasons that this has to be a comonad; the structure is given by projection and diagonal maps. Moreover, $\mathbb N_+[X]$ is a monad, the functor $X\mapsto X\times \mathbb N_+[X]$ being the product $\text{id}\times \mathbb N_+[-]$ in the category of monads on $\bf Set$.

Example. Every species $P$ defines an operad, the endomorphism operad, with carrier $\{P,P\}$ (notation as in the construction of the internal hom for $\circ$); the unit is the mate of the left unitor $y(1)\circ P \to P$, and the multiplication is obtained as the mate of the counit of $-\circ P\dashv \{P,-\}$:

Associativity and unitality follow from the adjunction identities of $-\circ P\dashv \{P,-\}$. In particular, if $P$ is constant at a set $P_0$, one has $\{P,P\}(m) = {\bf Set}(P^m_0,P_0)$.

Example. There is an operad structure on the terminal object $E : n\mapsto{\ast}$ of set-species $\bf Spc$, but this is not very interesting (the structure is trivially given by the unique map $E\circ E \to E$, $y(1) \to E$ into $E$). Instead, on $k$-vector species, the operad $\boldsymbol k[E] : n\mapsto \boldsymbol k$ constant at the 1-dimensional space carries the structure of an operad as follows: first, observe that $k[E]\circ k[E] = \int^m k[E]m\otimes k[E]^{\ast m} \cong \int^m k\otimes k[E^{\ast m}]$; this (plus the fact that $k[-]$ is strong monoidal) reduces the problem to the computation of the iterated Day convolution of $E$ with itself. A type of $E^{\ast m}(n)$ structure now consists of a $m$-partition on $n$ in the terminology of the red book, i.e. an ordered partition of $n$ into $m$ (possibly empty) disjoint subsets (so: $E^{\ast m}\cong {\bf Set}(-,m)$ with the action of a permutation defined as $f\mapsto f\circ \sigma^{-1}$); $E^{\ast m}$ is called the species $\text{Par}^{[m]}$ of $m$-partitions.

The operad structure is once again obtained simply (but not completely trivially) by setting the multiplication as the map

sending $(\alpha;\beta_1,\dots, \beta_m)$ to $\alpha\beta_1\cdots\beta_m$ (product in $\boldsymbol k$).

The species of nonempty sets also carries a structure of (set, and $k$-vector) operad, which in some respect is more interesting; the same reasoning can be repeated, until the characterization of $E_+^{\ast m}$ is due. In the terminology of the red book, a species of $E_+^{\ast m}$-structure on $n$ consists of an $m$-ballot, i.e. an unordered partition into nonempty subsets of $n$. The resulting species is denoted $\text{Bal}^{[k]}$. Here is a picture:

As simple as this may seem, the terminal species with its unique $\circ$-monoid structure plays a fundamental role in the theory of operads; one should think of the unique element $a_n\in E(n)$ as a unique “$n$-ary abstract operation”, as depicted in this figure:

Exercise. Use the associativity property of ${\tt Com}$ to prove that “$a_2$ is associative”, in the sense that the diagram

commutes for a certain choice of object $[?]$; which one? It is tedious to make this precise, but you should take it as a mandala exercise.

Example. The operad ${\tt As}$ with carrier $L$ is obtained as the “natural” operad structure on $L=\sum_{n\ge 0} y(n)$; the unit is given by the first coprojection $\text{in}_1 : y(1)\hookrightarrow \sum_{n\ge 0} y(n)$, and since $L\circ L\cong \sum_{n\ge 0} L^{\ast n}$, to define a multiplication $L\circ L\to L$ it is enough to define a map of species $L^{\ast n} \to L$; this can be done to the effect that in components, the multiplication $\mu_{\tt As}$ is defined as

sends $(\sigma ; \tau_1 , \dots, t_m)$ to the shuffle $\tau_{\sigma 1} \mathbin{ш} \dots \mathbin{ш} \tau_{\sigma m}$.

Example. A different operad structure (the operad ${\tt Zinb}$) over $L_+$. The Zinbiel operad, denoted as ${\tt Zinb}$, is a ($k$-vector) operad that encodes the structure of a “Zinbiel algebra”. The name of the operad is a whimsical reversal of the name “Leibniz,” attributed to a virtual mathematician. A Zinbiel algebra is defined as a vector space $A$ equipped with a binary operation $\prec$ that satisfies the fundamental Zinbiel relation: $(x \prec y) \prec z = x \prec (y \prec z + z \prec y)$.

The underlying species of ${\tt Zinb}$ is the group algebra of the symmetric group $K[\Sigma_n]$, that is the $k$-vector space over the basis $L_+(n)$. This implies that the dimension of ${\tt Zinb}(n)$ is exactly $n!$. The operadic composition in ${\tt Zinb}$ can be described combinatorially; given a partition $X$ of a set $I$, the composition yields the sum of all linear orders $l$ on $I$ such that the restriction of $l$ to each block $S \in X$ matches the prescribed orders on those blocks, and the order induced by $l$ on the set of minimum elements of those blocks matches the order on the partition $X$ itself.

Example. The ${\tt Lie}$ operad. The underlying species of the $k$-vector operad whose algebras (in the sense of ref) are Lie algebras is a fundamentally new object. Suppose $x_\bullet = \{x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots\}$ is a countably infinite set of variables. ${\tt Lie}(n)$ is the vector space spanned by all the “bracket sequences” in the elements $\{x_1,\dots,x_n\}$ (or just $\{1,\dots,n\}$ for short) —parenthesized arrangements where each element of $\{x_1,\dots,x_n\}$ appears exactly once, which can be parametrized as binary trees, which are then subject to the relations generated by antisymmetry and the Jacobi identity. For example, ${\tt Lie}(2)$ is the set of bracketings $\{[1,2],[2,1]\}$ modded out by the relation $[2,1]=-[1,2]$, and ${\tt Lie}(3)$ is the set containing $\{[i,j] \mid i < j\}$ as well as $[i,[j,k]]$ for all $i,j,k$, subject to the Jacobi relation

The operad structure on ${\tt Lie}$ is obtained from the fact that binary trees can be grafted onto each other, and that this grafting operation respects the quotient by antisimmetry and Jacobi. If an element $b_m \in {\tt Lie}(m)$ (say, $b_4$ is the equivalence class of $[[1,[2,3]],4]$) is the equivalence class of a bracketing of $1,\dots,m$, and we are given bracketings $t_1,\dots, t_m$ (say, $t_1=[1,[2,3]]$, $t_2=[[1,2],[[3,4],5]]$, $t_3=[1,2]$, $t_4=[[[1,2],3],4]$) then

is a bracketing of $3+5+2+4=14$ symbols (a certain care is needed to make this precise, much like it’s needed some care in making precise the substitution of a $\lambda$-term inside another…)

We can summarize the situation in a table:

| Operad | Carrier | |

|---|---|---|

| ${\tt Com}, {\tt Com}_+$ | $E, E_+$ | (terminal, nonempty terminal) |

| ${\tt As}, {\tt As}_+$ | $L, L_+$ | (linear orders, nonempty linear orders) |

| ${\tt Zinb}$ | $L_+$ | (nonempty linear orders) |

| ${\tt Perm}$ | $J$ | (species of elements) |

| ${\tt Lie}$ |